The lesser prairie chicken is a medium-sized, gray-brown ground dwelling bird that is part of the grouse family. They can be anywhere between 38 and 41 cm long and have a short, rounded tail. The lesser prairie chicken is found in the Southwest region of the United States, living in the Great Plains area where they have access to vast native grasslands and areas of low growing brush. The lesser prairie chicken was listed as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) in 2014.

A 2015 court order later overturned the Services’ decision, noting that a “threatened” designation was unnecessary due to efforts by states, industry, and landowners to preserve the bird’s habitat. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service later issued a final rule officially removing the “threatened” status for the species. Several wildlife conservation groups later petitioned in November 2016 for the species to be considered for an emergency endangered listing. The agency is now required to make a decision as to whether a listing is appropriate within twelve months of reviewing the petition, with a decision expected in late November 2017. The Service also expects to issue a notice of proposed rulemaking on the listing petition in September.

Why is the lesser prairie chicken being considered again for listing?

Efforts to list the lesser prairie chicken are focused on concerns on habitat and fragmentation of native grasslands. Given the short lifespan of the lesser prairie chicken, nesting is extremely important for the species. The grouse will only nest in large tracks of native grasslands and prairies, and is particularly sensitive to infrastructure changes and drought in the region.

According to a survey released in June 2017 by the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (WAFWA), the lesser prairie-chicken population is remaining stable, with an increase in the estimated breeding population over the last year. While the agency said fluctuations from year-to-year are to be expected and typically due to changes in weather patterns, the results are a strong indication of conservation efforts underway.

Roger Wolfe, WAFWA’s Lesser Prairie Chicken Program Manager, stated “the bottom line is that the population trend over the last five years indicates a stable population, which is good news for all involved in lesser prairie-chicken conservation efforts.”

Where is the lesser prairie chicken located?

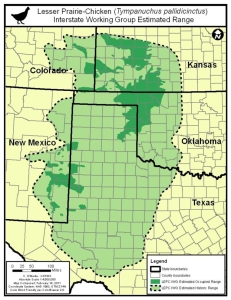

The lesser prairie chicken currently occupies a five-state range in the Southwest region of the United States. The species’ range includes the following states: Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas.

Click here for a list of U.S. counties in the lesser prairie chicken’s range.

What is being done to help the lesser prairie chicken?

Over the past two decades, governments, industry, and numerous state and local partners have dedicated time and resources to protect and conserve the habitat of the lesser prairie chicken. This includes efforts by FWS, such as:

- 1995: FWS receives petition to list the lesser prairie chicken as “threatened” under the ESA.

- 1998: FWS status review determines that listing the less prairie chicken was warranted, but precluded under the ESA.

- 2011: FWS status review determines that listing the lesser prairie chicken was warranted, but still precluded under the ESA.

- December 2012: FWS status review leads to proposed rule to list the lesser prairie chicken as threatened under the ESA.

- May 2013: FWS proposes to take measures to conserve the lesser prairie chicken under the 4(d) rule of the ESA and opens the comment period.

- March 2014: FWS announces the final listing of the species as threatened, as well as a final special rule under section 4(d) of the ESA.

In January 2017, IPAA submitted joint comments that the best scientific and commercial information available demonstrates that the chicken does not meet the ESA’s definitions of either a threatened or endangered species. As outlined in the comments, lesser prairie chicken abundance has rebounded from historic lows, and through a combination of public and private efforts, the species is now better protected than at any previous time.

What is a 4(d) rule?

A 4(d) rule is one of many tools provided by the Endangered Species Act to allow for flexibility in the Act’s implementation and to customize regulations to those that make the most sense for protecting and managing at-risk species. The goal of a 4(d) rule is to ensure private landowners and citizens are not impacted by regulations that do not further the conservation of the species and, when conducting certain activities, are exempted from “take” prohibitions (defined in the ESA as to harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, etc.). This rule may be applied only to species listed as threatened and directs the Fish and Wildlife Service to issue regulations deemed “necessary and advisable to provide for the conservation of threatened species.”

On May 6, 2013, the FWS published a proposed 4(d) rule for the lesser prairie chicken and reopened the public comment period on the proposal to list the lesser prairie chicken as a threatened species under the ESA. In March 2014, FWS listed the lesser prairie chicken as threatened and announced the final 4(d) rule, establishing a range-wide conservation plan for the lesser prairie chicken “to mitigate any unavoidable impacts of a particular activity on the lesser prairie chicken and provid{ing} financial incentives to landowners who voluntarily participate and manage their property for the benefit of the lesser prairie-chicken.” According to the 4(d) rule for the bird, “incidental to activities conducted by a participant enrolled in, and operating in compliance with, the Lesser Prairie Chicken Interstate Working Group’s Lesser Prairie Chicken Range-Wide Conservation Plan (rangewide plan) will not be prohibited.”

Since this time, a 2015 court order overturned the Services’ decision to list the bird, noting that a “threatened” designation was unnecessary due to efforts by states, industry, and landowners to preserve the bird’s habitat. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has since issued a final rule officially removing the “threatened” status for the species.

What is the oil and gas industry doing to help the lesser prairie chicken?

FWS, state wildlife agencies, private landowners and corporations are working together on a number of efforts to preserve the lesser prairie chicken’s habitat. Energy companies, namely members of the oil and gas industry, are committed to this effort through conservation agreements and easements aimed at limiting the impact on the prairie chicken.

For example, a voluntary conservation mechanism has been implemented to allow oil and gas companies to access the bird’s habitat areas if the company enrolls in the range-wide conservation plan with the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (WAFWA). According to recent news reports, “for every acre of development by an oil and gas company two acres are set apart for chicken conservation.”

According to a report from the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (WAWFA) regarding the Lesser Prairie Chicken Range-wide Conservation Plan, in the plan’s initial year, the lesser prairie chicken range-wide population increased by over 20 percent and landowners conserved nearly 40,000 acres of habitat. According to the survey, industry partners, including 181 energy, electric, and oil and natural gas companies, have committed $45.9 million in fees by enrolling in mitigation agreements with WAWFA. Impacted habitats have also decreased by 23 percent as a result of the consolidation of oil and gas development projects, and the agencies have authorized about 700 project agreements to offset the impact of development on the lesser prairie chicken population. As WAFWA’s grassland coordinator Bill Van Pelt describes, the survey demonstrates “that both industry and landowners are willing to conserve the species.”

Companies have also implemented new technologies to limit surface impacts and improve site restoration, including the use of horizontal drilling, greatly diminishing the number of wells required to produce the same amount of oil and natural gas resources. In addition, companies have adapted equipment to mirror the surrounding environment and consolidated operations to limit surface disruptions.

What now for the lesser prairie chicken?

A 12-month finding from the Fish and Wildlife Service is expected in the fall of 2017 on whether or not a re-listing of the bird is warranted. The previous removal of the listing of the lesser prairie chicken has been cheered by many given the obstacles a federal listing put in place, including impacts on private landowners, farmers, ranchers, transportation projects and oil and gas production. Sen. Inhofe (R-OK) praised the decision, remarking “The agency’s original listing was rushed and failed to properly take into consideration the facts on the ground.” Re-implementing a threatened listing will not provide any additional conservation benefits above what already exists.

Check out more news about the lesser prairie chicken on ESA Watch HERE.