The greater sage-grouse is a large, ground-dwelling bird with round wings and distinct pointed tail feathers. The birds can be up to 30 inches long and two feet tall and can weigh between two and seven pounds. The greater sage-grouse is found in the Western region of the United States, typically in areas with an elevation between 4,000 and 9,000 feet that are well-populated with sagebrush. The Fish and Wildlife Service announced in September 2015 the grouse does not warrant protection under the Endangered Species Act. The Service simultaneously announced final plans governing land use activities on millions of acres of federally managed sagebrush habitat in 10 Western states.

Why is the greater sage-grouse a candidate for ESA protection?

According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), the greater sage-grouse population is threatened by the encroachment of invasive vegetation, such as cheatgrass, that makes sagebrush, the primary source of food and shelter for the greater sage-grouse, susceptible to frequent wildfires. While sagebrush can resist extreme environmental conditions, most species of sagebrush are killed by fire. Specifically at risk are “leks,” the areas where male sage-grouse gather to perform displays of courtship in approximation to nesting areas. Nest success is dependent on having an undisturbed sagebrush-populated area. The greater sage-grouse and other native wildlife species depend on the preservation of these unique western sage-steppe habitats, and the risk of a shifting landscape poses a threat to the bird’s population.

Where is the greater sage-grouse located?

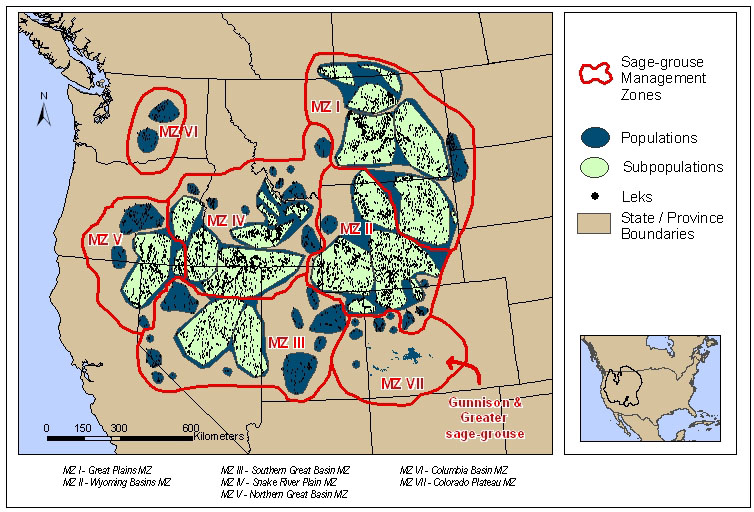

The greater sage-grouse is found across much of the western and northwestern United States as well as several Canadian provinces. The species’ range includes the following 11 states: Washington, Oregon, California, Nevada, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, South Dakota, and North Dakota.

Greater sage-grouse Management Zones with populations and sub-populations. Source: US Department of Interior

What is being done to help the greater sage-grouse?

FWS, in addition to numerous state and local stakeholders, is actively looking at ways to protect and conserve the habitat of the greater sage-grouse. Over the past 12 years, numerous steps have been taken to determine whether the grouse warrants federal protection.

- 1999 through 2003: FWS received 8 petitions to list the greater sage-grouse throughout all or parts of its range.

- January 2005: Initial range-wide finding that the species was not-warranted for listing under the Endangered Species Act.

- 2007: FWS decision was challenged, and the decision was remanded to the FWS.

- 2010: FWS status review determined that listing the sage-grouse was warranted, but precluded under the Endangered Species Act. The Sage-Grouse Initiative (SGI) was launched by the U.S. Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service.

- January 2013: FWS releases its draft assessment of the greater sage-grouse’s candidacy in cooperation with Wyoming state officials.

- May 2015: The Bureau of Land Management (BLM), FWS, and partners release a series of Environmental Impact Statements (EIS) to incorporate greater sage-grouse conservation measures into the land use plans for the lands they manage.

- September 22, 2015: Fish and Wildlife announces the greater sage-grouse does not warrant federal protection under the Endangered Species Act. The Service simultaneously announced federal land use plans to governing land use activities on millions of acres of federally managed sagebrush habitat in the West.

Over this time, numerous state-based plans have also been implemented to protect the sage grouse, such as Wyoming’s Sage-Grouse Core Area Program and Colorado’s Greater Sage-Grouse Conservation Plan. FWS does not have regulatory or management authority over the sage grouse except where the bird occurs on Service lands, such as National Wildlife Refuges, and FWS’s authorities on these properties are limited to habitat, while the states have full control of management of the birds themselves.

What is the oil and gas industry doing to help the greater sage-grouse?

Many companies have joined forces with state and federal agencies to implement projects to improve greater sage-grouse habitats and abide by existing state-based conservation plans. One leading independent company, for example, runs an annual conservation and restoration project in the Powder River Basin alongside BLM and the Wyoming Conservation Corps to thin and remove invasive trees across priority sage-grouse habitat on BLM lands.

Companies have also implemented new technologies to limit surface impacts and improve site restoration. Thanks to the use of horizontal drilling, for example, oil and gas producers are now able to access energy reserves miles away from the well pad in various directions, greatly diminishing the number of wells required to produce the same amount of energy. In addition, many companies in the region are adapting equipment to mirror the surrounding environment, reducing the visual disturbance to the natural habitat, and consolidating their operations to limit surface disruptions. After operations are complete, oil and gas producers execute rigorous reclamation plans – ensuring the well pad area is restored to its original state.

IPAA has actively commented on the greater sage-grouse decision and process, including in an Op-Ed in The Hill and a press release on the listing announcement. IPAA President Barry Russell has also been featured in the Salt Lake Tribune and Casper Star-Tribune, highlighting the key role of states in the conservation of the grouse.

What do these federal plans mean for the greater sage-grouse?

While this non-warranted decision for the greater sage-grouse was expected, and recognizes the immense efforts already underway, these federal land use plans and their impact on energy development must still be addressed. The Interior’s greater sage-grouse conservation plan permits federal government overreach for the purpose of “implementing surface disturbance caps on development, minimizing surface occupancy from energy development, and identifying buffer distances around leks.” These “one size fits all” restrictions are projected to impact two million acres of land in the West, where federal oil and gas leasing has already dropped significantly under the Obama Administration.

The federal plan also undermines those put in place by state regulators. Many of the states impacted by these federal plans are also home to job-creating oil and natural gas projects. While these companies are actively working with state and local governments to protect the sage-grouse while continuing their operations, federal plans could limit future production and permitting in the region.

While every effort should be made to help restore the population of the greater sage-grouse in the Western region of the United States, it should not be done unnecessarily and at the expense of our economy and highly regulated oil and gas activities. The federal government should work with all stakeholders to reach a balanced approach that provides regulatory certainty, so that energy and economic development can coexist with the sage-grouse and its habitat.